As consumers grapple with brands saying they care about the planet, CEOs recognize their organizations’ responsibilities to society, and as employees seek meaning beyond the bottom line, companies are evolving to incorporate purpose into their identities.

In some cases, purpose runs deep. Others are faking it.

In “Purpose Orientation: An emerging theory transforming business for a better world,” faculty from the CSU College of Business Department of Marketing investigate the rapidly evolving nature and role of organizational purpose in the marketplace. Researchers Christopher Blocker, Joe Cannon and Jonathan Zhang examine purpose through the eyes of leaders across a diverse set of industries to offer new and fresh ideas for purpose.

Across several years of study, they found many companies seeking to evolve from a 20th-century focus on competing for customers and market share for the bottom line to a modern orientation that places grand challenges such as fighting the climate crisis, eliminating poverty and promoting sustainable communities at the center of why they exist, who they are and what they do.

The paper, which was published by The Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, articulates the internal and external tensions companies face when adopting a sense of larger purpose.

“Purpose Orientation: An emerging theory transforming business

for a better world”

Christopher Blocker, Joseph Cannon, Jonathan Zhang

The Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science

Some of those challenges are the stuff of advanced business courses: finding a purpose aligned with employee culture; authentically promoting that purpose without it coming off as a marketing stunt; the need for executives to be informed on issues outside their industry. Others dealt with more classic but thorny discussions around trading off profit margins in pursuit of environmental or social impact initiatives.

“Companies in many cases are shifting away from a profit maximization model and taking a longer-term view,” Blocker said. “Some of that is an investment in their brand, their people and in broader initiatives that help to compete in the long term. It may be a short-term cost in pursuit of longer-term principles and our values.”

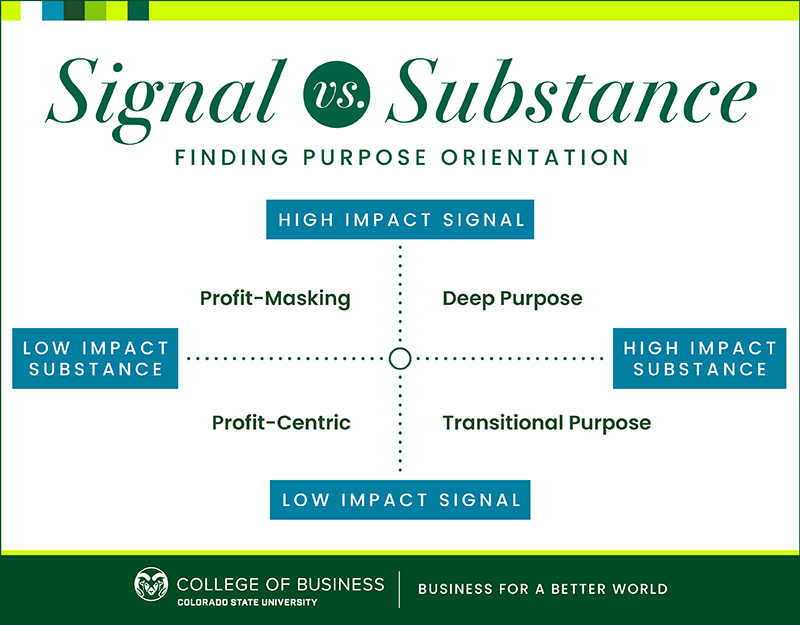

Signal vs. substance

Blocker, Cannon and Zhang identified two dimensions that define organizations’ use of purpose. The first, impact signal, captures how organizations communicate how their actions are promoting progress. The other, impact substance, is a measure of how much their investments are driving tangible positive impact, whether the public knows it or not. Together, they form a matrix with four sections, based on high and low degrees of signal and substance, that define models of purpose.

Profit-centric organizations are defined by low levels of substance and signal and are traditional organizations solely focusing on maximizing profit and see little value in pursuing a purpose.

The research defines organizations with low impact but high signaling – essentially those doing little but talking about it a lot – as profit-masking organizations. These companies opportunistically use purpose in branding efforts but aren’t truly engaged in substantive efforts for real impact and may draw charges of greenwashing from consumer groups.

“Most people are familiar with greenwashing,” Blocker said. “In these cases, companies are signaling that they want to help the world, but in reality, there’s not a lot going on behind the scenes that supports it. It’s mostly lip service or ingredient branding that produces a veneer of responsibility.”

Organizations with high commitment to their purpose but with low signaling are those with transitional purpose. These organizations have typically made the investment into defining and supporting their purpose but are waiting to communicate those efforts until it becomes more deeply ingrained in their culture and strategies.

“Firms here realize they need to give some time to say, ‘OK, we need to build up credibility and substance and then we can join the Patagonias of the world and be beacons for our purpose,’” Blocker said.

Finally, deep purpose organizations are those that have fully integrated their purpose into what they do, who they are and why they exist. These may be born-purposeful companies such many B-Corporation companies or well-known firms such as Patagonia, who have fully integrated purpose into their business ideology (logic), company culture (identity) and operations, messaging to customers and shareholders (strategy). Alternatively, they could be organizations such as Interface who, over many years, have shifted from a traditional profit-maximization purpose toward deep purpose.

“We find that purpose logic, identity and strategy are a three-legged stool,” Blocker said. “If you are using purpose strategy but you lack strong purpose logic or identity, you’re probably doing things that are akin to greenwashing. If you only have purpose logic, then you may have a leader committed to the environment or social development, but employees and the rest of the organization are disconnected from this purpose. If you only have purpose identity, you’re maybe a nonprofit or lack a business ideology.”

From theory to interviews

The findings build on a qualitative methodology known as theories-in-use, which orients emerging theories around individuals’ mental models that guide their behavior. Researchers delve into subjects’ actions and beliefs in an attempt to draw out a theory that explains specific behavior.

To do this, they spent two years interviewing 33 business leaders to determine how they view organizations’ purposes and how their companies are adopting that vision. This produced about 32,000 words, or 640 single-spaced pages, of transcripts. They also drew on popular press, podcasts and scholarly articles in which leaders talked about purpose in their business. From there, they applied qualitative coding that provide objective references to the subjective texts.

In addition to distilling the nature of purpose orientation, the research also indicates that many of the organizations examined are in flux. Companies categorized in profit-masking and transitional purpose states tended to be in the process of change, toward a deeper, more ingrained purpose or back to the traditional profit-driven mindset.

The path to Business for a Better World

The researchers hope the paper opens a new avenue about how academics and managers think about merging purpose and profit – as well as provide the tools for companies to transform their practices.

“This is a ground-breaking and emerging framework that could redefine and broaden business mindset and practice beyond just profit to larger societal purpose,” Zhang said. “It can ignite the discussion of how to define capitalism going forward.”

CSU’s College of Business is building a community of action-oriented leaders focused on using Business for a Better World through its leading-edge research, accessible education and top-rated undergraduate and graduate programs. Connecting the principles of people, planet, profit, and purpose across organizational business goals has earned the College global recognition, including being named one of five Best Business Schools in the world for responsible business education by Financial Times.